|

| The-Nesby-Tower-Branxholme-Scottish-Borders |

In 1590 he was knighted by James V1, king of Scotland, and appointed Keeper of Liddesdale. Sixteenth century Liddesdale, part of the Scottish Middle March, was the most dangerous place to live in the whole of Britain yet Scott accepted the role with self-assurance and alacrity. He knew he had the iron will, the power and the personality to subdue the unruly Border Reiver clans of Liddesdale-the Armstrongs, the Elliots, Crosers and Nixons.

In 1596 a Day of Truce was held between the Scots and English at the Dayholm of Kershope on the Border Line between England and Scotland.

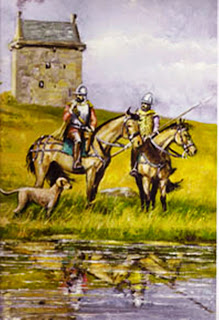

|

| The-Dayholme-of-Kershope |

Outwardly this Truce Day was but a minor affair as the trials to be heard were those of petty felons. As such deputy March Wardens were appointed to oversee and control the business of the day. Robert Scott of Haining presided for the Scots, Thomas Salkeld for the English.

The Day of Truce was always attended by both Scots and English to witness that each of the trials was conducted with both fairness and justice. Since 1583 the numbers had been limited to one hundred from each of the countries as previously the numbers were so large that the whole affair became uncontrollable. The trouble always centred on the fact that it was inevitable that among those asked to attend, mainly from the Border Reiving fraternity, there would be those who were at odds, often violent odds, with each other. English and Scots eyed each other with deep suspicion and hatred- the animosity a product of past raids and savage encounter. In an attempt to control those who attended it was written into Border Law that each man must swear that he would not offend ‘by word, deed or countenance’.

Conversely as many present would be wanted by the law and the law in the shape of the March Wardens their land-sergeants and bailliffs presided, a further enactment of Border Law was the ‘Assurance of the Truce’. Thus from sunrise of the Day of Truce until sunrise of the following day all men were considered beyond reproach, inviolate and untouchable unless they broke their own vow.

Sir Walter Scott had asked William Armstrong of Kinmont, the most notorious of the Scottish Border Reivers of the late sixteenth century, to attend. Kinmont was much prized by the English; his raids from Scotland into English Tynedale, Northumberland, often at the head of huge numbers from the Scottish Border valleys were particularly violent and vicious and resulted in death and maiming to those who endeavoured to contest the theft of vast numbers of cattle and sheep which were driven slowly back to the Scottish homelands.

At the Day of Truce at the Dayholme of Kershope many an eye filled with hatred viewed Kinmont with frustration that became a fixation. Present within yards was enemy number one of the English, yet he was untouchable under Border Law.

When the Truce had finished, before sunset, Kinmont set off for home with others going in the same direction: down the Kershope burn to its confluence with the river Liddel then onwards to Morton Rigg Tower.

|

| The-Kershope-Burn-Joins-the-River-Liddel |

Thomas Salkeld, English Deputy West March Warden and his retinue from Carlisle moved in the same direction but on the English bank of the river Liddel.

The temptation to capture Kinmont was too strong; he was the nearest he had been to the English for many a year. In unison both of thought and action, the English party turned their horses into the river, reached the Scottish bank and pursued Kinmont at pace. Near the confluence of the rivers Liddel and Esk Kinmont was taken, bound to his horse and, surrounded by Englishmen, moved stealthily onward to Carlisle and the dungeons of its castle.

Kinmont had been illegally taken by the English. They had violated the Border Law. The sun had not yet set. It was still hours to the rising of the sun on the day following the Day of Truce.

When news of the capture reached Sir Walter Scott he was incandescent with rage and immediately wrote to Thomas Salkeld demanding Kinmont’s release. The arguments that the capture provoked soon reached the ears of the monarchs of Scotland and England, James V1 and Elizabeth 1. The diplomatic wrangling that ensued produced no answers to issue; the English believed the capture was legal for a number of reasons including that Kinmont had violated the Truce whilst the Scots were adamant that it was definitely illegal.

After a month in which the diplomatic approach seemed only to achieve rancour, claim and counter claim, Sir Walter Scott decided that a more pro-active approach was called for.

In this he was greatly assisted by the English family of Grahams who had their own reasons for supporting Scott including the demise of the English West March Warden , Thomas Lord Scrope. The Grahams were truly “English at their will, Scottish at their leisure”. They were, without doubt, the most powerful of the English Border families. Not many men contested their stranglehold over the protection rackets and blackmail that were endemic in the Border lands.

After meetings at both a race meeting in Langholm in the Scottish Borders and dinner within Langholm castle, Scott and the Grahams decided that they would take the bull by the horns and endeavour to rescue Kinmont from Carlisle castle, the second strongest in the whole of the Border lands.

A veritable army would never succeed in reaching the castle unnoticed, not with the river Eden to cross, its main ford being the Eden bridges which was manned by professional soldiers twenty-four hours a day.

No, the plan demanded small numbers and stealth and there was twelve miles of English ground to encounter before Carlisle was to be reached. Small numbers could be at the mercy of any of the English Border Reiver families out on a raid in the area. However the Grahams let it be known that there would be no-one out on the prowl on the night chosen to head for Carlisle. They would see to that!

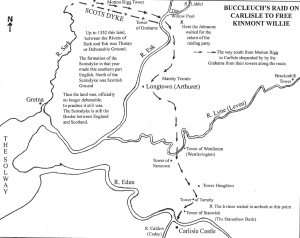

On the night of April 13th 1596 about eighty of the Scottish Border Reivers left Morton Rigg Tower and headed for Carlisle. Armstrongs, Irvines and Johnstons and Kinmont’s sons were among those who rode south. The weather was perfect for the campaign. The rain poured for the whole of the night ride southwards into England. There would be few folk abroad on such a night.

|

| Buccleuch’s-Raid-on-Carlisle |

Having reached the Scots Dyke (still the Border line between England and Scotland) the party of about twenty Johnsons reined their horses right and positioned themselves in the trees of the Debateable Lands. Their role was to be one of waiting for the return of the raiding party after the attempt to rescue Kinmont; shepherd them home to the lands of Ewesdale or ambush any English pursuers.

From the Scots Dyke the remainder of Scott’s raiders passed the towers of Westlevington, Houghton, Tarraby until they reached the tower of Stanwick on the Staneshaw Bank. As each was passed a light appeared in each signifying that the Grahams were on watch, ready to intervene should there be anyone to contest the party’s southern journey.

The Irvines, one formidably fierce Scottish Border clan of Reivers, now peeled away and concealed themselves in the wooded area of the Staneshaw, their role the same as the Johnsons.

Now there were just twenty or so left for the assault on the formidable pile of Carlisle castle, mainly Armstrongs and Kinmont’s sons. Scott urged his men forward, encouraged by the perverse weather as it continued to rain in mind-blowing sheets.

|

| Carlisle-Castle-Cumbria-England |

Cold and drenched the raiders reached the Eden bridges but knowing any attempt to assault and subdue its garrison would be futile, they moved to the west, reached the river Eden, dismounted and, without any ceremony, swam the raging river.

It is said that after approaching the castle with ladders to scale the walls, they found that they were too short and that the alternative of undermining a postern door in the western wall of the castle was undertaken.

( It is my belief that this was not the case. Earlier that year Thomas Lord Scrope had dismissed the captain of the castle, one Thomas Musgrave, a man in league with the Grahams. He still had men of his ilk working within the walls of the castle. I believe that one of his cronies watching out for the raiding party, opened the postern gate for the raiders).

Five of the raiding party entered the castle whilst the remainder, some twenty strong, stood outside the wall and created a carcophony of strident noise with drums and trumpets. It was to good effect. The garrison of the castle, hidden under tarpaulins to protect themselves from the foul weather, thought that a sizeable army was investing the castle and panicked.

The five raiders, with opposition from just two of the inmates of the castle who proved to be ineffective, were led to the room where Kinmont was warded and soon released him.

Soon the raiders with Kinmont in tow had re-crossed the river Eden, mounted their horses, and rode hard for the Border. Thomas Lord Scrope, West March Warden and his deputy, Thomas Salkeld endeavoured to gather some opposition to the audacious assault of the Scottish raiders but it was too late. They were away and joined by the Irvines at the Staneshaw Bank and the the Johnsons at the Scots Dyke.

Kinmont went into hiding until the heat had died down. It would not be for long.

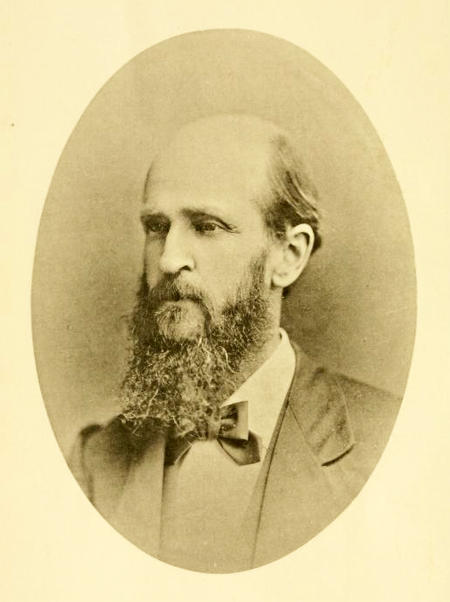

Sir Walter Scott was, without doubt, the outstanding character to walk and ride the Border lands of the sixteenth century. In his younger days he had proved himself to be a formidable Border Reiver but as the century moved on and he got older and wiser, he had the intelligence to see that the days of the Reiver were numbered.

In 1606 he was made the first Lord Buccleuch. He died in 1611 and was buried in St. Mary’s church in Hawick.